How to Cultivate Humor

If you're suffering depression, humor can change your state of mind.

by Nando Pelusi, Ph.D. via Psychology Today

Humor doesn't typically come to mind in the same breath as depression. But humor can be an important ally in getting beyond the rigidity of thinking that accompanies depression and keeps people locked into a depressed state of mind.

One goal of cognitive therapy is to change your perspective, your point of view. Humor is one way to change your view viscerally—and enjoyably.

Cultivating a humorous mindset helps you see yourself and any situation with a more supple mind so that you are not locked into a negative view. Depression is both caused by and causes the inability to see options and choices we otherwise would.

Take a common situation: someone feels very depressed in the wake of having failed at something. They cancel plans and withdraw from social opportunities. They don't feel "up to it." Under the surface, perhaps out of view of the conscious mind, the person might feel that the failure disqualifies him from the human race. However, turning around and asking out loud, "Does that disqualify me from the human race?" is humorous. It highlights the absurdity of the extreme conclusion.

We're not talking stand-up comedy, but insight-oriented commentary, achieved via anecdote and metaphor. You might feel down from a cutting remark your spouse made. But you could ask yourself: Does that "cutting" remark draw blood? Noting the metaphor puts it in its place—an obnoxious comment, but not a searing one.

Humor fosters acceptance of our humanness and our foibles. It is not sarcasm or put-downs. What we are looking for is gentle, playful perspective that embraces humanness but never at the expense of others—or of ourselves. The goal is not to take life too seriously.

So how to foster good humor?

Choose to allow yourself to laugh at your own behaviors and beliefs—but not at yourself. Make that distinction clearly.

See your life not as a distraught drama but as a romantic comedy. Recognize the inherent farce-like quality in situations including sex and relationships.

Cultivating humor not only makes life more bearable, it makes you more attractive to others. Study upon study shows that a sense of humor is high up on the list of traits that most people seek in a partner.

Insert silliness. Fill your life with one goofy thing a day. Make an unusual observation about someone. Or do something you normally wouldn't do. Wear something silly. You will learn that nothing terrible happens—and you may also discover that something good often happens.

Puncture a rigid mindset with a mental exercise called "paradoxical intention."

Suppose you have to give a speech and you are unduly anxious about looking uncomfortable. You can overcome the fear of failure by deliberately focusing on it and humorously exaggerating the very effects you fear.

Say you are worried about having to speak publicly and sweating profusely. Deliberately imagine a humorous situation where you are—literally—sweating like a fountain and spewing enough to drown the first row of the audience. Accept that you sweat like a fountain; imagine it and then think, what is the worst that could happen?

Exaggeration is funny because it skewers the falsehood. If you fail at a test or perform poorly at an audition, you could erroneously call yourself a failure. That, however, is an overgeneralization. Alternatively, you could see yourself as someone who failed at this particular thing, but in no way does that stamp you forever in this way.

Find the humor by saying, this makes me an utter wretch, a failure now and forever, a doomed and worthless subhuman, because I didn't get the part that I wanted or my partner isn't giving me the attention I want. Get into the exaggeration until you see the absurdity of seeing yourself as a "total failure."

Walk down the street remembering that people are nude under their clothes. It reduces fear of others. Such thoughts can take people of high status from deity to human. It helps to remember that everyone yells at their kids, spills ketchup, goes to the bathroom.

Play to an audience. Think of stories and items that would make others laugh.

Be sensitive to the words you use. They can rigidify or help loosen up your thinking.

Create cute, funny neologisms with your partner. Call it goofifying. Creating your own funny expressions for your experiences makes you more flexible and allows you to interpret and assess reality better.

Reactive Candy

The Journey of a 40 Something, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Depression: Coping With Anxiety Symptoms

WebMD Feature

By R. Morgan Griffin

Depression and anxiety might seem like opposites, but they often go together. More than half of the people diagnosed with depression also have anxiety.

Either condition can be disabling on its own. Together, depression and anxiety can be especially hard to live with, hard to diagnose, and hard to treat.

“When you’re in the grip of depression and anxiety, it can feel like the misery will never end, that you’ll never recover,” says Dean F. MacKinnon, MD, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “But people do recover. You just need to find the right treatment.”

The Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

Depression can make people feel profoundly discouraged, helpless, and hopeless. Anxiety can make them agitated and overwhelmed by physical symptoms -- a pounding heart, tightness in the chest, and difficulty breathing.

People diagnosed with both depression and anxiety tend to have

More severe symptoms

More impairment in their day-to-day lives

More trouble finding the right treatment

A higher risk of suicide

Tips for Depression and Anxiety Treatment

Depression and anxiety can be harder to treat than either condition on its own. Getting control might take more intensive treatment and closer monitoring, says Ian A. Cook, MD, the director of the Depression Research Program at UCLA. Here are some tips.

Give medicine time to work. Many antidepressants also help with anxiety. You might need other medicines as well. It could take time for the drugs to work -- and time for your doctor to find the ideal medicines for you. In the meantime, stick with your treatment and take your medication as prescribed.

Put effort into therapy. Although many types of talk therapy might help, cognitive behavioral therapy has the best evidence for treating anxiety and depression. It helps people identify and then change the thought and behavior patterns that add to their distress. Try to do your part: the benefit you’ll get from therapy is directly related to the work you put into it.

Make some lifestyle changes. As your treatment takes effect, you can do a lot on your own to reinforce it. Breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and yoga can help. So can the basics, like eating well, getting enough sleep, and exercising. The key is to figure out ways of integrating better habits into your life -- something that you can work on with your therapist.

Get a second opinion. When they're combined, depression and anxiety can be hard to diagnose. It's easy for a doctor to miss some of your symptoms -- and as a result, you could wind up with the wrong treatment. If you have any doubts about your care, it's smart to check in with another expert.

Focus on small steps. If you’re grappling with depression and anxiety, making it through the day is hard enough. Anything beyond that might seem impossible. “Changing your behavior can seem overwhelming,” Cook says. “I encourage people to make small, manageable steps in the right direction.” Over time, small changes can give you the confidence to make bigger ones.

Be an active partner in your treatment. There are many good ways to treat depression and anxiety. But they all hinge on one thing: a good relationship with your healthcare providers. Whether you see a GP, psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker -- or a combination -- you need to trust one another and work as a team.

By R. Morgan Griffin

Depression and anxiety might seem like opposites, but they often go together. More than half of the people diagnosed with depression also have anxiety.

Either condition can be disabling on its own. Together, depression and anxiety can be especially hard to live with, hard to diagnose, and hard to treat.

“When you’re in the grip of depression and anxiety, it can feel like the misery will never end, that you’ll never recover,” says Dean F. MacKinnon, MD, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. “But people do recover. You just need to find the right treatment.”

The Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety

Depression can make people feel profoundly discouraged, helpless, and hopeless. Anxiety can make them agitated and overwhelmed by physical symptoms -- a pounding heart, tightness in the chest, and difficulty breathing.

People diagnosed with both depression and anxiety tend to have

More severe symptoms

More impairment in their day-to-day lives

More trouble finding the right treatment

A higher risk of suicide

Tips for Depression and Anxiety Treatment

Depression and anxiety can be harder to treat than either condition on its own. Getting control might take more intensive treatment and closer monitoring, says Ian A. Cook, MD, the director of the Depression Research Program at UCLA. Here are some tips.

Give medicine time to work. Many antidepressants also help with anxiety. You might need other medicines as well. It could take time for the drugs to work -- and time for your doctor to find the ideal medicines for you. In the meantime, stick with your treatment and take your medication as prescribed.

Put effort into therapy. Although many types of talk therapy might help, cognitive behavioral therapy has the best evidence for treating anxiety and depression. It helps people identify and then change the thought and behavior patterns that add to their distress. Try to do your part: the benefit you’ll get from therapy is directly related to the work you put into it.

Make some lifestyle changes. As your treatment takes effect, you can do a lot on your own to reinforce it. Breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, and yoga can help. So can the basics, like eating well, getting enough sleep, and exercising. The key is to figure out ways of integrating better habits into your life -- something that you can work on with your therapist.

Get a second opinion. When they're combined, depression and anxiety can be hard to diagnose. It's easy for a doctor to miss some of your symptoms -- and as a result, you could wind up with the wrong treatment. If you have any doubts about your care, it's smart to check in with another expert.

Focus on small steps. If you’re grappling with depression and anxiety, making it through the day is hard enough. Anything beyond that might seem impossible. “Changing your behavior can seem overwhelming,” Cook says. “I encourage people to make small, manageable steps in the right direction.” Over time, small changes can give you the confidence to make bigger ones.

Be an active partner in your treatment. There are many good ways to treat depression and anxiety. But they all hinge on one thing: a good relationship with your healthcare providers. Whether you see a GP, psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker -- or a combination -- you need to trust one another and work as a team.

Saturday, March 2, 2013

Understanding Depression Disguises

Many people think of depression as an intolerable sadness or a deep gloom that just won't go away. Yet depression can also be sneaky, disguised in symptoms that can be hard to identify. If you've had unexplained aches or pains, often feel irritable or angry for no reason, or cry at the drop of a hat -- you could be depressed.

Fortunately, you can be proactive with depression. Learn how these less obvious symptoms can reveal themselves and when you should seek out depression treatment.

Common Depression Symptoms

Common symptoms of depression include feeling sad, hopeless, or empty or having lost interest in the things that previously gave you pleasure. But other, less obvious symptoms also may signal depression, including:

Anger, irritability, and impatience. You may feel irritated and angry at family, friends, or co-workers, or overreact to small things.

Sleep problems. You may have trouble sleeping, or you may wake up very early in the morning. Or you may sleep too much and find it hard to get up in the morning.

Anxiety. You may have symptoms such as anxiety, worry, restlessness, and tension. Anxiety and depression often occur together, even though they are two separate problems.

Crying. Crying spells, crying over nothing at all, or crying about small things that normally wouldn't bother you may be signs of depression.

Inability to concentrate. If you are depressed, you may be forgetful, have trouble making decisions, or find it hard to concentrate.

Pain. If you have aches and pains that don't respond to treatment, including joint pain, back pain, limb pain, or stomach pain, they could be signs of depression. Many people with depression go to their doctor because of these types of physical symptoms, and don't even realize that they are depressed.

Substance abuse. Having a drug or alcohol problem may hide an underlying problem with depression. Substance abuse and depression often go hand in hand.

Appetite changes. You may have no desire to eat, or you may overeat in an effort to feel better.

Isolation. You may feel withdrawn from friends and family -- right when you need their support the most.

Depression Symptoms: Men and Women May Differ

Not everyone has the same signs and symptoms of depression. In fact, men and women may experience depression differently. Women more often describe feeling sad, guilty, or worthless when they are depressed.

Men are more likely to feel tired, angry, irritable, and frustrated, and they often have more sleep problems. A man may feel less interested in hobbies, activities, and even sex. He may focus excessively on work in order to avoid talking with friends and family about how he feels. Men also may be more likely to behave recklessly and use drugs or alcohol to deal with depression. Some men with depression can become abusive. More women attempt suicide than men do, but men are more likely to succeed -- almost four times as many men die from suicide as do women.

Many men do not acknowledge feelings or symptoms of depression. They don't want to admit that something may be wrong or talk about their feelings. But men and women can both feel better with treatment.

Depression Symptoms: When to Seek Treatment

It can be hard to admit to yourself that you may be depressed, let alone ask for help. Here are two good reasons why you should consider depression treatment:

Treatment works. Even people with severe depression can find relief, and so can you.

Early treatment is better. As with many other health problems, getting treatment early on can ease symptoms more quickly. If you wait to get help, your depression can become more severe and harder to treat.

Talk to someone. There are many people willing to help you overcome depression, but the first step you have to take on your own is to let someone know how you are feeling. It may help to start by talking to a close friend or family member. Ask them for support in finding depression treatment. The sooner you get treatment, the sooner you will start to feel better. Don't hesitate -- call your doctor or a medical health professional if:

You think you may be depressed

You notice symptoms of depression such as sadness, hopelessness, or emptiness, or if you have less obvious symptoms such as trouble sleeping or vague aches and pains

Depression symptoms make it hard to function

If you have thoughts about dying or committing suicide, seek immediate medical help. You may feel hopeless now, but treatment will give you hope -- and help you see that life is worth living.

Depression Treatment: Give it Time to Work

Certain medications and medical conditions such as thyroid problems can cause symptoms of depression, so your doctor may want to rule them out. If your doctor thinks you may be depressed, he or she can refer you to a mental health professional.

Depression treatment involves either antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, or both. People with mild to moderate depression can benefit from therapy alone. People with more severe depression usually do better with medication and therapy. Note that once you start treatment, you may notice improvements in symptoms such as sleep or appetite before begin to you feel less depressed.

Antidepressants work by affecting brain chemicals called neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Antidepressants effectively treat depression in most people who take them. However, they can take four to six weeks to notice an effect, so it's important to be patient. Antidepressants can also have side effects, including weight gain and sexual problems. So it may take some time to find the right medication that works best for you with the fewest side effects.

Psychotherapy treats depression by helping you:

Learn new, more positive ways of thinking

Change habits or behaviors that may make your depression worse

Work through relationship problems at home or work

Help you see things in a more realistic way and face your fears

Help you feel hopeful, positive, and more in control of your life

It can take time to break old patterns of thinking and behavior, so give therapy some time to work.

Depression Treatment: How to Help Yourself

In addition to the help and support you get from your therapist and/or doctor, there are a few things you can do on your own that will help you feel better:

Stay physically active. Exercise helps boost your mood, and research has shown that it may also help ease depression.

Get a good night's sleep. Sleep helps us heal from many health problems, including depression. Getting the right amount of sleep, but not too much, helps you have more energy. Try to go to sleep and get up at the same time every day. Make your bedroom a comfortable place for sleeping and sex only -- banish TV and use curtains to keep out bright outdoor light.

Stay connected. Spending time with supportive friends or family will make you feel better -- even if you don't feel like it will. It may help to choose low-key ways to connect. Go to a light-hearted movie, meet for a coffee and some people watching, or take a walk in a nearby park. The contact you get from others, along with depression treatment, can help bring you out of the dark and back into the light.

© 2012 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved.

Fortunately, you can be proactive with depression. Learn how these less obvious symptoms can reveal themselves and when you should seek out depression treatment.

Common Depression Symptoms

Common symptoms of depression include feeling sad, hopeless, or empty or having lost interest in the things that previously gave you pleasure. But other, less obvious symptoms also may signal depression, including:

Anger, irritability, and impatience. You may feel irritated and angry at family, friends, or co-workers, or overreact to small things.

Sleep problems. You may have trouble sleeping, or you may wake up very early in the morning. Or you may sleep too much and find it hard to get up in the morning.

Anxiety. You may have symptoms such as anxiety, worry, restlessness, and tension. Anxiety and depression often occur together, even though they are two separate problems.

Crying. Crying spells, crying over nothing at all, or crying about small things that normally wouldn't bother you may be signs of depression.

Inability to concentrate. If you are depressed, you may be forgetful, have trouble making decisions, or find it hard to concentrate.

Pain. If you have aches and pains that don't respond to treatment, including joint pain, back pain, limb pain, or stomach pain, they could be signs of depression. Many people with depression go to their doctor because of these types of physical symptoms, and don't even realize that they are depressed.

Substance abuse. Having a drug or alcohol problem may hide an underlying problem with depression. Substance abuse and depression often go hand in hand.

Appetite changes. You may have no desire to eat, or you may overeat in an effort to feel better.

Isolation. You may feel withdrawn from friends and family -- right when you need their support the most.

Depression Symptoms: Men and Women May Differ

Not everyone has the same signs and symptoms of depression. In fact, men and women may experience depression differently. Women more often describe feeling sad, guilty, or worthless when they are depressed.

Men are more likely to feel tired, angry, irritable, and frustrated, and they often have more sleep problems. A man may feel less interested in hobbies, activities, and even sex. He may focus excessively on work in order to avoid talking with friends and family about how he feels. Men also may be more likely to behave recklessly and use drugs or alcohol to deal with depression. Some men with depression can become abusive. More women attempt suicide than men do, but men are more likely to succeed -- almost four times as many men die from suicide as do women.

Many men do not acknowledge feelings or symptoms of depression. They don't want to admit that something may be wrong or talk about their feelings. But men and women can both feel better with treatment.

Depression Symptoms: When to Seek Treatment

It can be hard to admit to yourself that you may be depressed, let alone ask for help. Here are two good reasons why you should consider depression treatment:

Treatment works. Even people with severe depression can find relief, and so can you.

Early treatment is better. As with many other health problems, getting treatment early on can ease symptoms more quickly. If you wait to get help, your depression can become more severe and harder to treat.

Talk to someone. There are many people willing to help you overcome depression, but the first step you have to take on your own is to let someone know how you are feeling. It may help to start by talking to a close friend or family member. Ask them for support in finding depression treatment. The sooner you get treatment, the sooner you will start to feel better. Don't hesitate -- call your doctor or a medical health professional if:

You think you may be depressed

You notice symptoms of depression such as sadness, hopelessness, or emptiness, or if you have less obvious symptoms such as trouble sleeping or vague aches and pains

Depression symptoms make it hard to function

If you have thoughts about dying or committing suicide, seek immediate medical help. You may feel hopeless now, but treatment will give you hope -- and help you see that life is worth living.

Depression Treatment: Give it Time to Work

Certain medications and medical conditions such as thyroid problems can cause symptoms of depression, so your doctor may want to rule them out. If your doctor thinks you may be depressed, he or she can refer you to a mental health professional.

Depression treatment involves either antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, or both. People with mild to moderate depression can benefit from therapy alone. People with more severe depression usually do better with medication and therapy. Note that once you start treatment, you may notice improvements in symptoms such as sleep or appetite before begin to you feel less depressed.

Antidepressants work by affecting brain chemicals called neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Antidepressants effectively treat depression in most people who take them. However, they can take four to six weeks to notice an effect, so it's important to be patient. Antidepressants can also have side effects, including weight gain and sexual problems. So it may take some time to find the right medication that works best for you with the fewest side effects.

Psychotherapy treats depression by helping you:

Learn new, more positive ways of thinking

Change habits or behaviors that may make your depression worse

Work through relationship problems at home or work

Help you see things in a more realistic way and face your fears

Help you feel hopeful, positive, and more in control of your life

It can take time to break old patterns of thinking and behavior, so give therapy some time to work.

Depression Treatment: How to Help Yourself

In addition to the help and support you get from your therapist and/or doctor, there are a few things you can do on your own that will help you feel better:

Stay physically active. Exercise helps boost your mood, and research has shown that it may also help ease depression.

Get a good night's sleep. Sleep helps us heal from many health problems, including depression. Getting the right amount of sleep, but not too much, helps you have more energy. Try to go to sleep and get up at the same time every day. Make your bedroom a comfortable place for sleeping and sex only -- banish TV and use curtains to keep out bright outdoor light.

Stay connected. Spending time with supportive friends or family will make you feel better -- even if you don't feel like it will. It may help to choose low-key ways to connect. Go to a light-hearted movie, meet for a coffee and some people watching, or take a walk in a nearby park. The contact you get from others, along with depression treatment, can help bring you out of the dark and back into the light.

© 2012 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved.

Friday, March 1, 2013

How Well Do You Function When Depressed?

WebMD Feature

By Denise Mann

You go to work every day and even make time to see your close friends and family on weekends. But for the most part, you’re really just spinning your wheels. Nothing seems to excite you anymore, and you look forward to climbing back into bed at the end of the day.

Sound familiar? Are you or a loved one able to function well every day, despite feeling depressed?

“These are people who are having symptoms of depression, but are able to get through tasks lifelessly,” says Scott Bea, PsyD. He is a psychologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Behavioral Health in Ohio. “You are basically just going through the motions without any enthusiasm.”

WebMD asked mental health experts to weigh in on how to manage depression proactively in order to thrive -- instead of just survive -- each day.

If you have severe depression, it can be difficult to get out of bed and you may withdraw from your friends and family. You may even become preoccupied with thoughts of death and dying, but this doesn’t happen overnight.

Many people with depression are able to work, maintain relationships, and manage their lives for a long time before it catches up with them. How can you tell if your symptoms are related to depression? The first step is to talk with your doctor and get help for depression.

Typical symptoms of depression may include:

Sleep problems

Physical aches and pains, such as headaches or back problems

Lack of energy

Difficulty concentrating

Feelings of guilt or worthlessness

Loss of interest in activities you previously enjoyed

Eating too much or not enough

Depression: This Too Shall Pass?

But ongoing symptoms of depression will pass eventually, right?

Not necessarily, Bea says. It may be tempting to just write these feelings off, but it doesn’t work that way. The first step is to own what is going on with you and take proactive steps to get out of the “funk.”

Some people ignore continuing depression symptoms and figure there’s nothing that can help. “We think we must merely endure these feelings and that something will give and we will feel better,” he says. It doesn’t work that way. “It will more likely get worse before it gets better,” he adds.

What can you do to cope? The next step is to shake things up a bit and make some lifestyle changes, Bea says.

Yes, it can be hard to make changes -- especially positive and healthful ones -- when you are feeling down. It is much easier to settle in on the couch and get lost in mindless TV than to go out for a walk or join a team, but you have to push yourself, he says.

“Create an obligation,” he says. “Sign up for a gym with a friend.”

For further motivation, reward your new habit by doing something that you like afterward.

“Get plugged back in to life,” Bea says. “Maybe even revisit something that you loved to do as a child, as a way to kick-start your engine.”

Be creative. “Think about the things that you loved at different times in life,” he says. You likely didn’t start feeling like this overnight, so it may take a while to get back in the game.

Depression: Taking Steps to Feel Better

When you’re depressed, it’s OK to “behave as if you are enthused and stop saying how difficult everything is,” Bea says.

Although lifestyle changes and picking up an old hobby can help, sometimes it’s simply not enough. Medication and counseling are also part of the solution, adds Bryan Bruno, MD. He is the acting chairman of psychiatry at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “If you are in therapy and things are getting worse, this is an indication that you should consider medication.”

Depression: Getting Support

You may already be on medication and still not feel like your usual self. If that’s the case, talk to your doctor if your current medications and treatment plan aren’t working.

“Sometimes more aggressive therapy is needed even if you are on medicine already,” says Bruno. Other options to help you cope with depression include:

Finding a depression support group. It can help to talk with others who are experiencing similar challenges.

Connecting online with other people who have depression.

Spending time with friends instead of being isolated and feeling alone.

Keeping a journal to help you monitor your moods and sharing it with your doctor.

Getting active. If you dread the thought of going to a gym -- and many people who feel depressed do -- consider trying a yoga class or taking a walk in the park to boost endorphins.

You don’t have to pretend that you feel good when you’re depressed. Talking to your doctor about ways to manage your depression -- and being honest about how you’re functioning -- can go a long way in feeling better long-term.

Thursday, February 7, 2013

How to Manage Depression Triggers with Mood-Boosting Strategy

WebMD Feature

By Denise Mann

Some people can take the “good” along with the “bad” in life, and mostly let things roll off of their shoulders. Others, however, are not quite as resilient. For them, any stressful life event -- whether the loss of a loved one, a dramatic break-up, or a layoff -- can kick-start a downward spiral.

If you have a personal or family history of depression, the key is to stop this spiral before it gets out of control by putting the clues and cues together. “If you know what your Achilles heels are and can say ‘Aha!” this is what is going on,’ you are halfway there,” says Gail Saltz, MD, a New York City-based psychiatrist.

No matter what triggers your depression, help is available. WebMD talked to mental health experts about the best things to do to help manage depression. Getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, and sleeping enough (but not too much) are good ways to take control of depression. A healthy lifestyle can help you head off depression, and will also help get you through a rocky patch.

But there’s more you can do, depending on your stressors. Here are some common depression-triggering scenarios and expert-approved mood-boosting strategies to help you cope:

Depression Trigger: Job Loss

In today’s unsteady economy, many people are losing their jobs. This can often lead to feelings of shame, worthlessness and depression -- especially in a person who is vulnerable.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Getting laid off doesn’t mean you are powerless, says Scott Bea, PsyD. He is a psychologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Behavioral Health in Ohio. Don’t take the news lying down. Seek employment counseling right away. “It is important to maintain social contact and connectedness,” he says. Don’t stop caring for yourself. You may be on a tight budget, but not everything has a steep price tag. “You can volunteer or coach a local softball team.” In short, “you need to find some way to make a difficult situation stimulate something new and better, rather than shutting down,” says Bea.

Depression Trigger: Empty Nest

Many women devote their lives to raising children, but that leaves them feeling as empty as their “nest” when their kids go off to college or begin their own life as an adult, says Saltz.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“Plan for it,” she says. “It can be the time for you to start taking classes, go back to school, or start a hobby,” she says. You are not alone. “Find other empty nesters for camaraderie.”

Depression Trigger: Caregiver Stress

There is a high rate of depression among people who take care of a loved one with a chronic illness, says Saltz. It can be physically and emotionally grueling.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

It’s not selfish to take care of yourself, says Saltz. “You need to eat well, sleep well, and get exercise or you will not be able to take care of your loved one,” she says. Many caregivers take on too much. “Be realistic about what your loved one needs and what you can provide,” she says. “Call in other family members to help. You don’t have to be the one and only.” Support groups for caregivers can also provide a safe place to talk about your frustrations.

Depression Trigger: Loss

Losing a loved one is never easy. Some people may be able to get past the loss after a certain amount of grieving time. Others may spiral into a deep depression.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Don’t go it alone, says Bea. “Join a support group.” Individual or group counseling can also help you come to terms with your loss. Medication may play a role too. If you are already on medication, it is possible that your doctor may want to adjust your dose or add another drug to help you get through a rough patch. “Help is available,” he says. Talk to your doctor about your depression to find the best treatment plan for you.

Depression Trigger: Marriage Problems/Divorce

It can be stressful and upsetting to be in a toxic relationship, but change and starting over can be scary -- even if you know it’s for the best, Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Some couples can benefit from marriage counseling, and it may even help save their relationship. If you are divorced or separated, support groups and individual therapy can help you get through the adjustment period and remember who you were before the split. “Give yourself some slack and seek support,” Saltz says.

Depression Trigger: Retirement

Yes, retirement is often idealized and even fantasized about. You and your spouse can take long leisurely walks on the beach, maybe take that dream vacation you always talked about, or even relocate to a warmer climate. “It is supposed to be joyful, but many retirees find themselves at loose ends and searching for an identity,” says Saltz. “When both spouses are together all day long, it can also it cause marital strife.”

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Don’t let yourself get bored, she says. Take classes, make plans with friends, and look for volunteer opportunities.

Depression Trigger: Hormonal Ups and Downs

Some women feel sad and irritable before their monthly period. Others have more severe mood symptoms during their time of the month. Older women may also experience some ups and downs as they approach menopause, and levels of the female sex hormone estrogen decline. Having a baby can also be a trigger. This can be a fleeting case of the baby blues or the more severe postpartum depression or postpartum psychosis. One common culprit in all of these scenarios are your hormones.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Keep a journal to see if you can identify any patterns, Saltz says. “If your mood changes and symptoms are impacting your life, treatments can help,” she says. “This may include therapy, self-talk, and deep breathing. “For women with severe premenstrual syndrome, medication may also be an option,” Saltz says. Postpartum depression is also treatable. If you are feeling sad, hopeless, and or having trouble caring for and bonding with your baby, talk to your doctor or a mental health professional right away.

Depression Trigger: Family Strife

While some people enjoy spending time with family, others may find it less than enjoyable. “Family get-togethers can rekindle childhood and child-like ways of interacting with one another,” Saltz says. “Any intense relationship tumult can alter your mood.”

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Just say no! “Make other plans and say, ‘This year, I can’t do it’.” If you are around your family, and feel that relatives are trying to rile you, don’t take the bait, she says. “Walk away.”

Depression Trigger: Holidays

For some, holidays are the loneliest days on the calendar. “Suicides peak during the holidays,” Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Reach out to others so you feel less alone. Volunteer at a soup kitchen or homeless shelter during the holidays. “Don’t have such a high threshold for asking for help,” Saltz says.

Depression Trigger: Winter Blues

If you notice that you begin to feel down each year when winter arrives, and the days grow shorter, it could be seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a type of depression that occurs during the same season each year.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“The good news is that SAD is treatable,” Saltz says. “Medication or light therapy, under a doctor’s direction, can help.” There is more you can do too. “You can also increase natural light by making it a point of doing work near a window – particularly in the morning,” she says. Exercise also helps improve symptoms of SAD. “Aim for 30 minutes of aerobic exercise multiple times a week.”

Depression Trigger: Anniversaries of Loss

Many people may feel depressed on or around the anniversary of a loss, almost as if it just happened or is happening all over again. “These are almost always triggers,” Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“When you know that an anniversary of loss is coming and that you are more likely to feel depressed, try to bolster your connectivity to people who are supportive,” she says. “Honor the anniversary, but don’t isolate yourself.”

By Denise Mann

Some people can take the “good” along with the “bad” in life, and mostly let things roll off of their shoulders. Others, however, are not quite as resilient. For them, any stressful life event -- whether the loss of a loved one, a dramatic break-up, or a layoff -- can kick-start a downward spiral.

If you have a personal or family history of depression, the key is to stop this spiral before it gets out of control by putting the clues and cues together. “If you know what your Achilles heels are and can say ‘Aha!” this is what is going on,’ you are halfway there,” says Gail Saltz, MD, a New York City-based psychiatrist.

No matter what triggers your depression, help is available. WebMD talked to mental health experts about the best things to do to help manage depression. Getting regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, and sleeping enough (but not too much) are good ways to take control of depression. A healthy lifestyle can help you head off depression, and will also help get you through a rocky patch.

But there’s more you can do, depending on your stressors. Here are some common depression-triggering scenarios and expert-approved mood-boosting strategies to help you cope:

Depression Trigger: Job Loss

In today’s unsteady economy, many people are losing their jobs. This can often lead to feelings of shame, worthlessness and depression -- especially in a person who is vulnerable.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Getting laid off doesn’t mean you are powerless, says Scott Bea, PsyD. He is a psychologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Behavioral Health in Ohio. Don’t take the news lying down. Seek employment counseling right away. “It is important to maintain social contact and connectedness,” he says. Don’t stop caring for yourself. You may be on a tight budget, but not everything has a steep price tag. “You can volunteer or coach a local softball team.” In short, “you need to find some way to make a difficult situation stimulate something new and better, rather than shutting down,” says Bea.

Depression Trigger: Empty Nest

Many women devote their lives to raising children, but that leaves them feeling as empty as their “nest” when their kids go off to college or begin their own life as an adult, says Saltz.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“Plan for it,” she says. “It can be the time for you to start taking classes, go back to school, or start a hobby,” she says. You are not alone. “Find other empty nesters for camaraderie.”

Depression Trigger: Caregiver Stress

There is a high rate of depression among people who take care of a loved one with a chronic illness, says Saltz. It can be physically and emotionally grueling.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

It’s not selfish to take care of yourself, says Saltz. “You need to eat well, sleep well, and get exercise or you will not be able to take care of your loved one,” she says. Many caregivers take on too much. “Be realistic about what your loved one needs and what you can provide,” she says. “Call in other family members to help. You don’t have to be the one and only.” Support groups for caregivers can also provide a safe place to talk about your frustrations.

Depression Trigger: Loss

Losing a loved one is never easy. Some people may be able to get past the loss after a certain amount of grieving time. Others may spiral into a deep depression.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Don’t go it alone, says Bea. “Join a support group.” Individual or group counseling can also help you come to terms with your loss. Medication may play a role too. If you are already on medication, it is possible that your doctor may want to adjust your dose or add another drug to help you get through a rough patch. “Help is available,” he says. Talk to your doctor about your depression to find the best treatment plan for you.

Depression Trigger: Marriage Problems/Divorce

It can be stressful and upsetting to be in a toxic relationship, but change and starting over can be scary -- even if you know it’s for the best, Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Some couples can benefit from marriage counseling, and it may even help save their relationship. If you are divorced or separated, support groups and individual therapy can help you get through the adjustment period and remember who you were before the split. “Give yourself some slack and seek support,” Saltz says.

Depression Trigger: Retirement

Yes, retirement is often idealized and even fantasized about. You and your spouse can take long leisurely walks on the beach, maybe take that dream vacation you always talked about, or even relocate to a warmer climate. “It is supposed to be joyful, but many retirees find themselves at loose ends and searching for an identity,” says Saltz. “When both spouses are together all day long, it can also it cause marital strife.”

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Don’t let yourself get bored, she says. Take classes, make plans with friends, and look for volunteer opportunities.

Depression Trigger: Hormonal Ups and Downs

Some women feel sad and irritable before their monthly period. Others have more severe mood symptoms during their time of the month. Older women may also experience some ups and downs as they approach menopause, and levels of the female sex hormone estrogen decline. Having a baby can also be a trigger. This can be a fleeting case of the baby blues or the more severe postpartum depression or postpartum psychosis. One common culprit in all of these scenarios are your hormones.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Keep a journal to see if you can identify any patterns, Saltz says. “If your mood changes and symptoms are impacting your life, treatments can help,” she says. “This may include therapy, self-talk, and deep breathing. “For women with severe premenstrual syndrome, medication may also be an option,” Saltz says. Postpartum depression is also treatable. If you are feeling sad, hopeless, and or having trouble caring for and bonding with your baby, talk to your doctor or a mental health professional right away.

Depression Trigger: Family Strife

While some people enjoy spending time with family, others may find it less than enjoyable. “Family get-togethers can rekindle childhood and child-like ways of interacting with one another,” Saltz says. “Any intense relationship tumult can alter your mood.”

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Just say no! “Make other plans and say, ‘This year, I can’t do it’.” If you are around your family, and feel that relatives are trying to rile you, don’t take the bait, she says. “Walk away.”

Depression Trigger: Holidays

For some, holidays are the loneliest days on the calendar. “Suicides peak during the holidays,” Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

Reach out to others so you feel less alone. Volunteer at a soup kitchen or homeless shelter during the holidays. “Don’t have such a high threshold for asking for help,” Saltz says.

Depression Trigger: Winter Blues

If you notice that you begin to feel down each year when winter arrives, and the days grow shorter, it could be seasonal affective disorder (SAD), a type of depression that occurs during the same season each year.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“The good news is that SAD is treatable,” Saltz says. “Medication or light therapy, under a doctor’s direction, can help.” There is more you can do too. “You can also increase natural light by making it a point of doing work near a window – particularly in the morning,” she says. Exercise also helps improve symptoms of SAD. “Aim for 30 minutes of aerobic exercise multiple times a week.”

Depression Trigger: Anniversaries of Loss

Many people may feel depressed on or around the anniversary of a loss, almost as if it just happened or is happening all over again. “These are almost always triggers,” Saltz says.

Mood-Boosting Strategy

“When you know that an anniversary of loss is coming and that you are more likely to feel depressed, try to bolster your connectivity to people who are supportive,” she says. “Honor the anniversary, but don’t isolate yourself.”

Wednesday, February 6, 2013

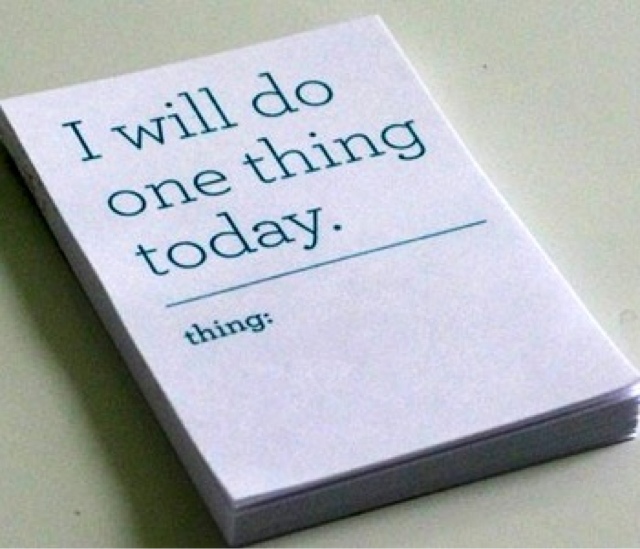

One Thing To Do Today - February 6, 2013

One Thing To Do Today: Use less water, turn off a light or do some other small thing to help the environment

Tuesday, February 5, 2013

One Thing To Do Today - February 5, 2013

One Thing To Do Today: Relationships with family are one of the most important things in life. Take ten uninterrupted minutes today to bette

Monday, February 4, 2013

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Saturday, February 2, 2013

Friday, February 1, 2013

Thursday, January 31, 2013

Understanding Depression Disguises

Via WebMd

Many people think of depression as an intolerable sadness or a deep gloom that just won't go away. Yet depression can also be sneaky, disguised in symptoms that can be hard to identify. If you've had unexplained aches or pains, often feel irritable or angry for no reason, or cry at the drop of a hat -- you could be depressed.

Fortunately, you can be proactive with depression. Learn how these less obvious symptoms can reveal themselves and when you should seek out depression treatment.

Common Depression Symptoms

Common symptoms of depression include feeling sad, hopeless, or empty or having lost interest in the things that previously gave you pleasure. But other, less obvious symptoms also may signal depression, including:

Anger, irritability, and impatience. You may feel irritated and angry at family, friends, or co-workers, or overreact to small things.

Sleep problems. You may have trouble sleeping, or you may wake up very early in the morning. Or you may sleep too much and find it hard to get up in the morning.

Anxiety. You may have symptoms such as anxiety, worry, restlessness, and tension. Anxiety and depression often occur together, even though they are two separate problems.

Crying. Crying spells, crying over nothing at all, or crying about small things that normally wouldn't bother you may be signs of depression.

Inability to concentrate. If you are depressed, you may be forgetful, have trouble making decisions, or find it hard to concentrate.

Pain. If you have aches and pains that don't respond to treatment, including joint pain, back pain, limb pain, or stomach pain, they could be signs of depression. Many people with depression go to their doctor because of these types of physical symptoms, and don't even realize that they are depressed.

Substance abuse. Having a drug or alcohol problem may hide an underlying problem with depression. Substance abuse and depression often go hand in hand.

Appetite changes. You may have no desire to eat, or you may overeat in an effort to feel better.

Isolation. You may feel withdrawn from friends and family -- right when you need their support the most.

Depression Symptoms: Men and Women May Differ

Not everyone has the same signs and symptoms of depression. In fact, men and women may experience depression differently. Women more often describe feeling sad, guilty, or worthless when they are depressed.

Men are more likely to feel tired, angry, irritable, and frustrated, and they often have more sleep problems. A man may feel less interested in hobbies, activities, and even sex. He may focus excessively on work in order to avoid talking with friends and family about how he feels. Men also may be more likely to behave recklessly and use drugs or alcohol to deal with depression. Some men with depression can become abusive. More women attempt suicide than men do, but men are more likely to succeed -- almost four times as many men die from suicide as do women.

Many men do not acknowledge feelings or symptoms of depression. They don't want to admit that something may be wrong or talk about their feelings. But men and women can both feel better with treatment.

Depression Symptoms: When to Seek Treatment

It can be hard to admit to yourself that you may be depressed, let alone ask for help. Here are two good reasons why you should consider depression treatment:

Treatment works. Even people with severe depression can find relief, and so can you.

Early treatment is better. As with many other health problems, getting treatment early on can ease symptoms more quickly. If you wait to get help, your depression can become more severe and harder to treat.

Talk to someone. There are many people willing to help you overcome depression, but the first step you have to take on your own is to let someone know how you are feeling. It may help to start by talking to a close friend or family member. Ask them for support in finding depression treatment. The sooner you get treatment, the sooner you will start to feel better. Don't hesitate -- call your doctor or a medical health professional if:

You think you may be depressed

You notice symptoms of depression such as sadness, hopelessness, or emptiness, or if you have less obvious symptoms such as trouble sleeping or vague aches and pains

Depression symptoms make it hard to function

If you have thoughts about dying or committing suicide, seek immediate medical help. You may feel hopeless now, but treatment will give you hope -- and help you see that life is worth living.

Depression Treatment: Give it Time to Work

Certain medications and medical conditions such as thyroid problems can cause symptoms of depression, so your doctor may want to rule them out. If your doctor thinks you may be depressed, he or she can refer you to a mental health professional.

Depression treatment involves either antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, or both. People with mild to moderate depression can benefit from therapy alone. People with more severe depression usually do better with medication and therapy. Note that once you start treatment, you may notice improvements in symptoms such as sleep or appetite before begin to you feel less depressed.

Antidepressants work by affecting brain chemicals called neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Antidepressants effectively treat depression in most people who take them. However, they can take four to six weeks to notice an effect, so it's important to be patient. Antidepressants can also have side effects, including weight gain and sexual problems. So it may take some time to find the right medication that works best for you with the fewest side effects.

Psychotherapy treats depression by helping you:

Learn new, more positive ways of thinking

Change habits or behaviors that may make your depression worse

Work through relationship problems at home or work

Help you see things in a more realistic way and face your fears

Help you feel hopeful, positive, and more in control of your life

It can take time to break old patterns of thinking and behavior, so give therapy some time to work.

Depression Treatment: How to Help Yourself

In addition to the help and support you get from your therapist and/or doctor, there are a few things you can do on your own that will help you feel better:

Stay physically active. Exercise helps boost your mood, and research has shown that it may also help ease depression.

Get a good night's sleep. Sleep helps us heal from many health problems, including depression. Getting the right amount of sleep, but not too much, helps you have more energy. Try to go to sleep and get up at the same time every day. Make your bedroom a comfortable place for sleeping and sex only -- banish TV and use curtains to keep out bright outdoor light.

Stay connected. Spending time with supportive friends or family will make you feel better -- even if you don't feel like it will. It may help to choose low-key ways to connect. Go to a light-hearted movie, meet for a coffee and some people watching, or take a walk in a nearby park. The contact you get from others, along with depression treatment, can help bring you out of the dark and back into the light.

Many people think of depression as an intolerable sadness or a deep gloom that just won't go away. Yet depression can also be sneaky, disguised in symptoms that can be hard to identify. If you've had unexplained aches or pains, often feel irritable or angry for no reason, or cry at the drop of a hat -- you could be depressed.

Fortunately, you can be proactive with depression. Learn how these less obvious symptoms can reveal themselves and when you should seek out depression treatment.

Common Depression Symptoms

Common symptoms of depression include feeling sad, hopeless, or empty or having lost interest in the things that previously gave you pleasure. But other, less obvious symptoms also may signal depression, including:

Anger, irritability, and impatience. You may feel irritated and angry at family, friends, or co-workers, or overreact to small things.

Sleep problems. You may have trouble sleeping, or you may wake up very early in the morning. Or you may sleep too much and find it hard to get up in the morning.

Anxiety. You may have symptoms such as anxiety, worry, restlessness, and tension. Anxiety and depression often occur together, even though they are two separate problems.

Crying. Crying spells, crying over nothing at all, or crying about small things that normally wouldn't bother you may be signs of depression.

Inability to concentrate. If you are depressed, you may be forgetful, have trouble making decisions, or find it hard to concentrate.

Pain. If you have aches and pains that don't respond to treatment, including joint pain, back pain, limb pain, or stomach pain, they could be signs of depression. Many people with depression go to their doctor because of these types of physical symptoms, and don't even realize that they are depressed.

Substance abuse. Having a drug or alcohol problem may hide an underlying problem with depression. Substance abuse and depression often go hand in hand.

Appetite changes. You may have no desire to eat, or you may overeat in an effort to feel better.

Isolation. You may feel withdrawn from friends and family -- right when you need their support the most.

Depression Symptoms: Men and Women May Differ

Not everyone has the same signs and symptoms of depression. In fact, men and women may experience depression differently. Women more often describe feeling sad, guilty, or worthless when they are depressed.

Men are more likely to feel tired, angry, irritable, and frustrated, and they often have more sleep problems. A man may feel less interested in hobbies, activities, and even sex. He may focus excessively on work in order to avoid talking with friends and family about how he feels. Men also may be more likely to behave recklessly and use drugs or alcohol to deal with depression. Some men with depression can become abusive. More women attempt suicide than men do, but men are more likely to succeed -- almost four times as many men die from suicide as do women.

Many men do not acknowledge feelings or symptoms of depression. They don't want to admit that something may be wrong or talk about their feelings. But men and women can both feel better with treatment.

Depression Symptoms: When to Seek Treatment

It can be hard to admit to yourself that you may be depressed, let alone ask for help. Here are two good reasons why you should consider depression treatment:

Treatment works. Even people with severe depression can find relief, and so can you.

Early treatment is better. As with many other health problems, getting treatment early on can ease symptoms more quickly. If you wait to get help, your depression can become more severe and harder to treat.

Talk to someone. There are many people willing to help you overcome depression, but the first step you have to take on your own is to let someone know how you are feeling. It may help to start by talking to a close friend or family member. Ask them for support in finding depression treatment. The sooner you get treatment, the sooner you will start to feel better. Don't hesitate -- call your doctor or a medical health professional if:

You think you may be depressed

You notice symptoms of depression such as sadness, hopelessness, or emptiness, or if you have less obvious symptoms such as trouble sleeping or vague aches and pains

Depression symptoms make it hard to function

If you have thoughts about dying or committing suicide, seek immediate medical help. You may feel hopeless now, but treatment will give you hope -- and help you see that life is worth living.

Depression Treatment: Give it Time to Work

Certain medications and medical conditions such as thyroid problems can cause symptoms of depression, so your doctor may want to rule them out. If your doctor thinks you may be depressed, he or she can refer you to a mental health professional.

Depression treatment involves either antidepressant medication, psychotherapy, or both. People with mild to moderate depression can benefit from therapy alone. People with more severe depression usually do better with medication and therapy. Note that once you start treatment, you may notice improvements in symptoms such as sleep or appetite before begin to you feel less depressed.

Antidepressants work by affecting brain chemicals called neurotransmitters that regulate mood. Antidepressants effectively treat depression in most people who take them. However, they can take four to six weeks to notice an effect, so it's important to be patient. Antidepressants can also have side effects, including weight gain and sexual problems. So it may take some time to find the right medication that works best for you with the fewest side effects.

Psychotherapy treats depression by helping you:

Learn new, more positive ways of thinking

Change habits or behaviors that may make your depression worse

Work through relationship problems at home or work

Help you see things in a more realistic way and face your fears

Help you feel hopeful, positive, and more in control of your life

It can take time to break old patterns of thinking and behavior, so give therapy some time to work.

Depression Treatment: How to Help Yourself

In addition to the help and support you get from your therapist and/or doctor, there are a few things you can do on your own that will help you feel better:

Stay physically active. Exercise helps boost your mood, and research has shown that it may also help ease depression.

Get a good night's sleep. Sleep helps us heal from many health problems, including depression. Getting the right amount of sleep, but not too much, helps you have more energy. Try to go to sleep and get up at the same time every day. Make your bedroom a comfortable place for sleeping and sex only -- banish TV and use curtains to keep out bright outdoor light.

Stay connected. Spending time with supportive friends or family will make you feel better -- even if you don't feel like it will. It may help to choose low-key ways to connect. Go to a light-hearted movie, meet for a coffee and some people watching, or take a walk in a nearby park. The contact you get from others, along with depression treatment, can help bring you out of the dark and back into the light.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Who Says Stress is Bad For You?

Another great article I stumbled upon using my SuperBetter app, that I had to share with my readers.

Via http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2009/02/13/who-says-stress-is-bad-for-you.html

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you aren't already paralyzed with stress from reading the financial news, here's a sure way to achieve that grim state: read a medical-journal article that examines what stress can do to your brain. Stress, you'll learn, is crippling your neurons so that, a few years or decades from now, Alzheimer's or Parkinson's disease will have an easy time destroying what's left. That's assuming you haven't already died by then of some other stress-related ailment such as heart disease. As we enter what is sure to be a long period of uncertainty—a gantlet of lost jobs, dwindling assets, home foreclosures and two continuing wars—the downside of stress is certainly worth exploring. But what about the upside? It's not something we hear much about.

In the past several years, a lot of us have convinced ourselves that stress is unequivocally negative for everyone, all the time. We've blamed stress for a wide variety of problems, from slight memory lapses to full-on dementia—and that's just in the brain. We've even come up with a derisive nickname for people who voluntarily plunge into stressful situations: they're "adrenaline junkies."

Sure, stress can be bad for you, especially if you react to it with anger or depression or by downing five glasses of Scotch. But what's often overlooked is a common-sense counterpoint: in some circumstances, it can be good for you, too. It's right there in basic-psychology textbooks. As Spencer Rathus puts it in "Psychology: Concepts and Connections," "some stress is healthy and necessary to keep us alert and occupied." Yet that's not the theme that's been coming out of science for the past few years. "The public has gotten such a uniform message that stress is always harmful," says Janet DiPietro, a developmental psychologist at Johns Hopkins University. "And that's too bad, because most people do their best under mild to moderate stress."

The stress response—the body's hormonal reaction to danger, uncertainty or change—evolved to help us survive, and if we learn how to keep it from overrunning our lives, it still can. In the short term, it can energize us, "revving up our systems to handle what we have to handle," says Judith Orloff, a psychiatrist at UCLA. In the long term, stress can motivate us to do better at jobs we care about. A little of it can prepare us for a lot later on, making us more resilient. Even when it's extreme, stress may have some positive effects—which is why, in addition to posttraumatic stress disorder, some psychologists are starting to define a phenomenon called posttraumatic growth. "There's really a biochemical and scientific bias that stress is bad, but anecdotally and clinically, it's quite evident that it can work for some people," says Orloff. "We need a new wave of research with a more balanced approach to how stress can serve us." Otherwise, we're all going to spend far more time than we should stressing ourselves out about the fact that we're stressed out.

When I started asking researchers about "good stress," many of them said it essentially didn't exist. "We never tell people stress is good for them," one said. Another allowed that it might be, but only in small ways, in the short term, in rats. What about people who thrive on stress, I asked—people who become policemen or ER docs or air-traffic controllers because they like seeking out chaos and putting things back in order? Aren't they using stress to their advantage? No, the researchers said, those people are unhealthy. "This business of people saying they 'thrive on stress'? It's nuts," Bruce Rabin, a distinguished psychoneuroimmunologist, pathologist and psychiatrist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told me. Some adults who seek out stress and believe they flourish under it may have been abused as children or permanently affected in the womb after exposure to high levels of adrenaline and cortisol, he said. Even if they weren't, he added, they're "trying to satisfy" some psychological need. Was he calling this a pathological state, I asked—saying that people who feel they perform best under pressure actually have a disease? He thought for a minute, and then: "You can absolutely say that. Yes, you can say that."

This kind of statement might well have the father of stress research lying awake worried in his grave. Hans Selye, who laid the foundations of stress science in the 1930s, believed so strongly in good stress that he coined a word, "eustress," for it. He saw stress as "the salt of life." Change was inevitable, and worrying about it was the flip side of thinking creatively and carefully about it, something that only a brain with a lot of prefrontal cortex can do well. Stress, then, was what made us human—a conclusion that Selye managed to reach by examining rats.

Selye had virtually no lab technique, and, as it turned out, that was fortunate. As a young researcher, he set out to study what happened when he injected rats with endocrine extracts. He was a klutz, dropping his animals and chasing them around the lab with a broom. Almost all his rats—even the ones he shot up with presumably harmless saline—developed ulcers, overgrown adrenal glands and immune dysfunction. To his credit, Selye didn't regard this finding as evidence he had failed.Instead, he decided he was onto something.

Selye's rats weren't responding to the chemicals he was injecting. They were responding to his clumsiness with the needle. They didn't like being dropped and poked and bothered. He was stressing them out. Selye called the rats' condition "general adaptation syndrome," a telling term that reflected the reason the stress response had evolved in the first place: in life-or-death situations, it was helpful.

For a rat, there's no bigger stressor than an encounter with a lean and hungry cat. As soon as the rat's brain registers danger, it pumps itself up on hormones—first adrenaline, then cortisol. The surge helps mobilize energy to the muscles, and it also primes several parts of the brain, temporarily improving some types of memory and fine-tuning the senses. Thus armed, the rat makes its escape—assuming the cat, whose brain has also been flooded with stress hormones by the sight of a long-awaited potential meal, doesn't outrun or outwit it.

This cascade of chemicals is what we refer to as "stress." For rats, the triggers are largely limited to physical threats from the likes of cats and scientists. But in humans, almost anything can start the stress response. Battling traffic, planning a party, losing a job, even gaining a job—all may get the stress hormones flowing as freely as being attacked by a predator does. Even the prospect of future change can set off our alarms. We think, therefore we worry.

Herein lies a problem. A lot of us tend to flip the stress-hormone switch to "on" and leave it there. At some point, the neurons get tired of being primed, and positive effects become negative ones. The result is the same decline in health that Selye's rats suffered. Neurons shrivel and stop communicating with each other, and brain tissue shrinks in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which play roles in learning, memory and rational thought. "Acutely, stress helps us remember some things better," says neuroendocrinologist Bruce McEwen of Rockefeller University. "Chronically, it makes us worse at remembering other things, and it impairs our mental flexibility."

These chronic effects may disappear when the stressor does. In medical students studying for exams, the medial prefrontal cortex shrinks during cram sessions but grows back after a month off. The bad news is that after a stressful event, we don't always get a month off. Even when we do, we may spend it worrying ("Sure, the test is over, but how did I do?"), and that's just as biochemically bad as the original stressor. This is why stress is linked to depression and Alzheimer's; neurons weakened by years of exposure to stress hormones are more susceptible to killers. It also suggests that those of us with constant stress in our lives should be reduced to depressed, forgetful wrecks. But most of us aren't. Why?

Step away from the lab, and you'll find the beginnings of an answer. In the 1970s and '80s, Salvatore Maddi, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, followed 430 employees at Illinois Bell during a companywide crisis. While most of the workers suffered as their company fell apart—performing poorly on the job, getting divorced and developing high rates of heart attacks, obesity and strokes— a third of them fared well. They stayed healthy, kept their jobs or found others quickly. It would be easy to assume these were the workers who'd grown up in peaceful, privileged circumstances. It would also be wrong. Many of those who did best as adults had had fairly tough childhoods. They had suffered no abuse or trauma but "maybe had fathers in the military and moved around a lot, or had parents who were alcoholics," says Maddi. "There was a lot of stress in their early lives, but their parents had convinced them that they were the hope of the family—that they would make everyone proud of them—and they had accepted that role. That led to their being very hardy people." Childhood stress, then, had been good for them—it had given them something to transcend.

More recently, Robert Sapolsky of Stanford University has studied a similar phenomenon in alpha males. He's seen plenty of "totally insane son of a bitch" types who respond to stress by lashing out, but he's also interested in another type that gets less press: the nice guy who finishes first. These alphas don't often get into fights; when they do, they pick battles they know they can win. They're just as dominant as their angry counterparts, and they're subject to the same stressors—power struggles, unsuccessful sexual overtures, the occasional need to slap down a subordinate—but their hormone levels never get out of whack for long, and they probably don't suffer much stress-induced brain dysfunction.Sapolsky likes to joke that they've all been relaxing in hot tubs in Big Sur, transforming themselves into "minimalist Zen masters." This is a joke because they've clearly come by their attitudes unconsciously: Sapolsky studies wild baboons.

Sapolsky's and Maddi's work points to a flaw with much of the neurobiological research: so far, it has done a poor job of accounting for differences in how individuals process stress. Researchers haven't identified the point at which the effects of stress tip over from positive to negative, and they know little about why that point differs from person to person. (This is why they don't like to tell people that a little stress can be good, says Rabin—because "we don't know how to judge for each individual what a 'little' stress is.") The research thus tends to paint stress as a universal phenomenon, even though we all experience it differently. "If there are rats or mice or cultured neurons in a dish that seem superresilient to stress, far too many lab scientists view this as a pain in the ass, something that just throws off patterns," says Sapolsky. "It's only people who are tuned into animal behavior or humans and the real world who are interested in how amazing the outliers are." Explaining these outliers' healthy attitudes, says Sapolsky, is now "the field's biggest challenge."

As Maddi's work makes clear, a lot of the explanation stems from early experiences. This may be true of Sapolsky's baboons as well. Sapolsky suspects that part of what makes an animal a dominant Zen master instead of an angry alpha lies in what sort of childhood he had. If an adult baboon picks up on conflict around him but keeps his cool, "quelling the anxiety and exercising impulse control," that may be behavior his mom modeled for him years earlier. The key? Factors such as how many steps the baby baboon could take away from his mother before she pulled him back—i.e., how much she allowed him to learn for himself, even if that meant a few bumps and bruises along the way. "I think the males who had mothers who were less anxious, who allowed them to be more exploratory in the absence of agitated maternal worry, are more likely to be the Zen ones who are calm enough to resist provocation," he says. A little properly handled stress, then, may be necessary to turn children into well-adjusted adults.

Part of the explanation will also be found in genes. Scientists have already identified one that helps control how the brain processes serotonin; some variants seem to protect people from depression, depending on whether they've suffered through previous traumas. This gene may not mediate everyday stress, but others are bound to be fingered eventually, and "once people have found scores of genes," says Sapolsky, "I'm willing to bet the farm that that's going to begin to explain who gets depressed after disastrous unrequited love and who just feels lousy for two weeks."

The X and Y chromosomes also play a role in how people respond to stress, though how much of one isn't clear. Men and women both experience stress as a rise in adrenaline and cortisol. What differs is their reaction. Women "are more likely to turn to their social networks, and that prompts the release of oxytocin, which mutes the stress systems," says Shelley Taylor, a psychologist at UCLA. If they're surrounded by loved ones when a stressor arises, she says, "there's some evidence they don't even show as much of the initial hormonal response." Without that response, there's less risk of long-term harm to the brain. It's a critical concept—yet it wasn't on stress physiologists' radar until the mid-'90s, when Taylor pointed out that most stress research in animals and humans had been conducted overwhelmingly on males.

Finally, there's that murky territory where genes and environment interact, with lifelong effects: the womb. It's not hard to find studies suggesting that maternal stress harms later child development. But what the evidence means, no one knows. "Project Ice Storm," a survey of nearly 150 expectant mothers who toughed out a 1998 squall in Quebec—some without power for up to 40 days—is one of the scariest studies. Late last year researchers reported that the women's children had lower-than-average IQs and language skills at age 5; they say the storm and its stress on the mothers had "significant effects [on the children] … in every area of development that we have examined." The study surveys many children in great detail, but it doesn't mean all pregnant women should panic about their stress levels (or panic about the fact that they've just panicked). An ice storm isn't the same kind of stressor that people encounter in everyday life, and the women in the ice-storm study don't necessarily represent all women. Those who were stuck in Quebec during the storm were likely some of the ones with the fewest resources. Their children may have been prone to low scores as 5-year-olds simply because they were poor.